How Does Reading Happen?

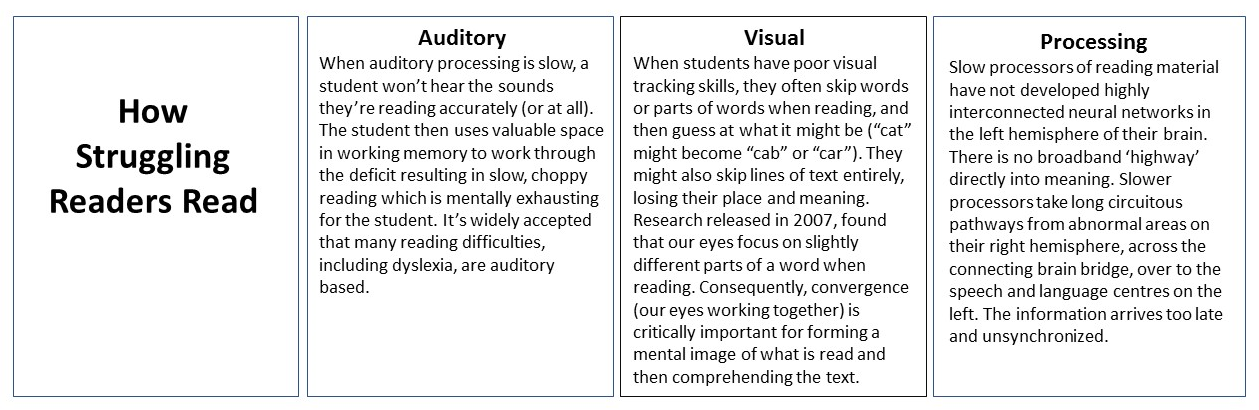

Brain imaging research shows that poor readers have fewer reading brain circuits and in the wrong places. This makes reading laborious and too slow for good comprehension. Remedial reading alone will rarely fix this problem. A brain plasticity intervention like Cellfield is required.

Beginner readers use the parieto-temporal of the brain to read. They have to decode and identify each word individually, which causes them to read slowly, one-word-at-a-time. On the other hand, experienced readers use different neural pathways to read: the occipto temporal area of the brain. Skilled readers have automatised all the basic skills needed for reading, and can go directly from what their eyes see to meaning.

Readers who get stuck at the parieto-temporal stage are stuck for neural reasons and will never be able to read fluently. Their working memories are permanently overloaded with lower order skills that they just can’t automatize, so they can’t make the transition to becoming a skilled reader. Cellfield has been developed to help these readers create new neural pathways and transition to becoming skilled readers.

Printed text is speech converted into visual symbols. Reading is the conversion of visual symbols back into speech. Children are born pre-programmed to develop listening and speaking skills naturally, but the need to read came very late in our evolutionary history. Our brains have not had time to develop reading skills naturally. Reading needs to be taught and mastered layer by layer, starting with simple skills, then working up to higher level ones. Some children learn to read by themselves. Most need some help, and some cannot manage at all.

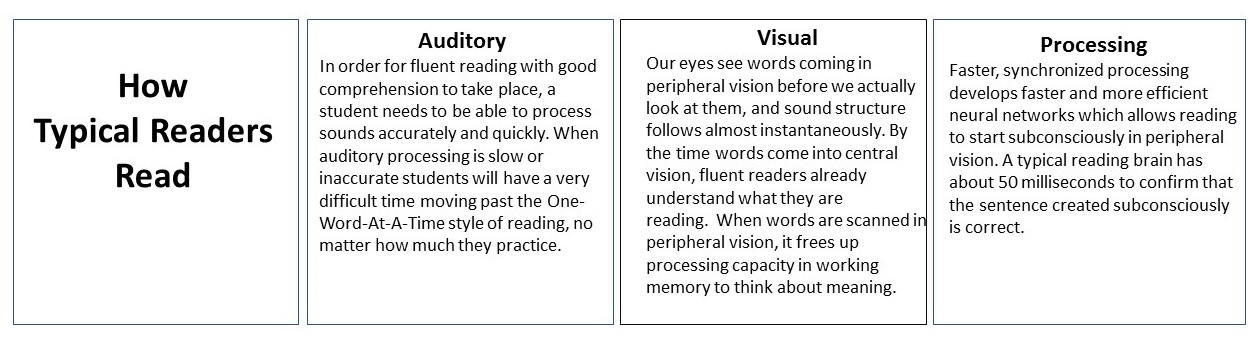

The ultimate goal of reading is being able to read fluently with good comprehension. Good comprehension requires accurate and rapid reading rate, so that a child can hold a sentence together, long enough to make sense of it.

Typical readers, who have mastered multiple layers of essential skills, have developed highly interconnected neural networks near the speech and language areas, in the left hemisphere of their brain. These networks function like a high speed broadband connection converting what the eyes see directly into meaning without the reader having to think about it..

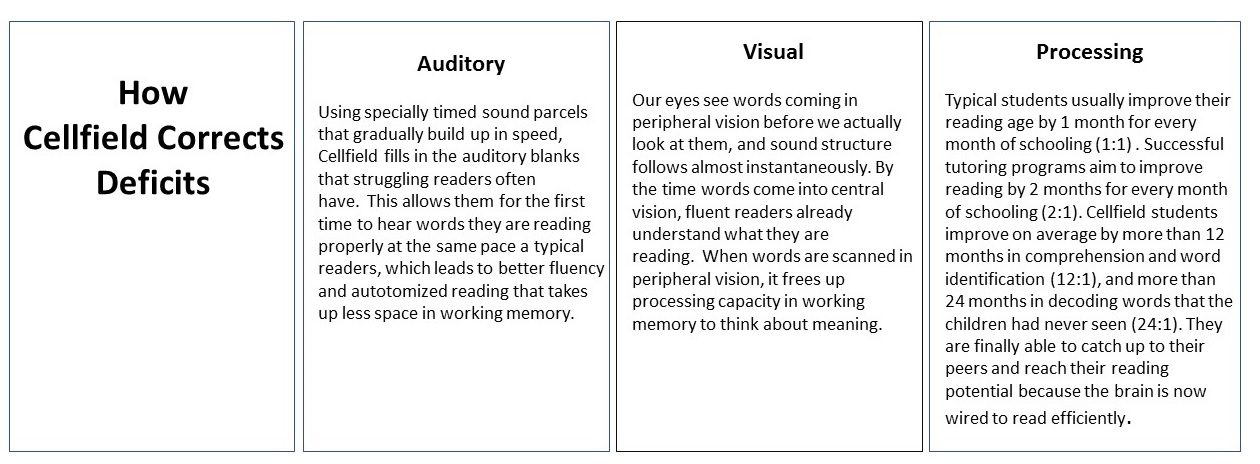

How Struggling Readers Read – When the Wrong Pathways are Bonded Reading is Hard – There Are Numerous Factors At Play.

The ultimate goal of reading is to be able to read fluently with good comprehension. Good comprehension requires accurate and rapid reading rate, so that a child can hold a sentence together long enough to make sense out it. Poor readers are slow processors of reading material, so by the time they get to the middle, they have forgotten the beginning and by the time they reach the end they have forgotten the middle and the beginning. The sentence they start putting together keeps falling apart, causing them to keep going back and starting again. This is called “˜dropout’.

What is Working Memory?

We use our working memory to learn and master new skills, which has very limited capacity. Once we learn something, we can use it without having to use our working memory, that is, without having to think about it.

Our brain tries to use working memory efficiently, by limiting the time that any particular material can stay in it. It removes the material when the subconscious brain decides the material is no longer novel. For poor readers, the reading material is moved out of working memory before they can master it. It disappears into their subconscious, into neural bins of “˜bits and pieces’.

ONCE CONNECTIONS ARE MADE, READING CAN BE LEARNED SMOOTHLY – CELLFIELD CREATES CONNECTIONS

Centuries of belief that all humans are “˜hard wired’ has resulted in a mainstream approach of compensating for dyslexia, rather than facing it head on. Brain imaging research has shown consistent differences in how dyslexic brains are wired compared to typical readers. Brain plasticity research has shown that our brains are plastic, and that when stimulated appropriately, can change.

Cellfield trains the dyslexic brain to read more efficiently. A 2009 Cellfield study performed at the University of Tasmania, recorded neural activity during reading, using Event Related Potentials (ERP) methods. ERP results indicated neural changes only within the Cellfield group, which shifted activity from the right hemisphere to the left hemisphere “suggesting, at least neurally, a partial return to language processing which more closely resembles that of (typical) readers”.